Executive summary

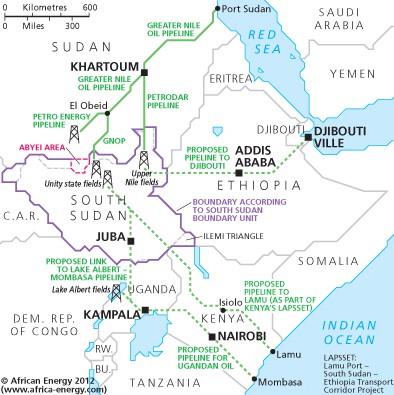

Reports that construction of an alternative oil pipeline from South Sudan to Port Lamu, Kenya, will begin in October 2013 are overly optimistic and on-schedule pipeline construction is unlikely. Despite delays and ongoing barriers to project construction, Juba is highly likely to continue pursuing alternatives to the existing pipeline to Port Sudan, Sudan. Such alternatives, if constructed, would have significant economic and political impacts on South Sudan, Sudan, China, and Kenya, Ethiopia and other potential pipeline partners.

I. Likelihood of alternate oil pipelines from South Sudan

South Sudan’s oil is currently exported via a pipeline to Port Sudan on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, essentially allowing Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir to control the flow. However, reports that construction of a $5-6 billion (USD), 2,000km alternate oil pipeline from South Sudan’s oil fields to Port Lamu, Kenya, will start in October 2013 are overly optimistic. On-schedule pipeline construction is unlikely given:

- outstanding feasibility studies and environmental assessments still require formal consideration, evaluation and review,

- project financing is yet to be identified,

- further intergovernmental agreements are incomplete, and

- another route – to Port of Djibouti – remains on the table.

Important macro-environmental factors in this assessment include:

- Alternate pipeline economics are likely to remain weak, unless current oil reserve estimates for South Sudan fields are increased by new discoveries or discoveries in Kenya and Uganda support integrated pipeline infrastructure.

- The majority of existing oil buyers are highly likely to support use of the existing pipeline to Port Sudan (unless strategically-sited reserves are discovered within South Sudan, east Uganda or northwest Kenya).

- Exploration activities and pipeline construction are likely to be difficult, given continuing armed conflict and the numbers of internally displaced persons (IDP) in Jonglei, South Sudan.

- Project costs could possibly increase given the significant environmental and geotechnical challenges that will almost certainly be identified in feasibility studies.

However, continuing distrust between Juba and Khartoum is highly likely and oil transportation diversification is likely to remain a core South Sudan national interest. Juba is therefore highly likely to continue to seek alternative pipeline routes. Important factors in this regard include:

- New discoveries in South Sudan and oil production infrastructure development in Ugandan or northwest Kenyan fields would almost certainly substantially improve project economics and political support for regional pipeline infrastructure.

- Political objectives linked with East African market integration, regional trading and integrated infrastructure development could possibly override concerns about weak project economics.

- Increasing Chinese investment in the Lamu Port and Lamu-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) projects could possibly weaken Chinese preference for using the existing pipeline to Port Sudan at full capacity.

- Pipeline risks from intercommunal violence, infrastructure sabotage and project-related conflict across Kenya is currently relatively low (in a regional context), making this a comparatively attractive export route.

II. Stakeholder impact of alternate pipeline construction and operation

In the event of alternate pipeline construction and eventual operation, possible scenarios for key stakeholders would be:

South Sudan

South Sudan would need to manage problems associated with tying limited funds up in supporting pipeline construction as opposed to more diverse economic and critical service sector development if the lack of external financiers continues; address conflict, displacement and rebel groups in Jonglei and Unity; and face a hardened bargaining position from Khartoum on Abyei.

Sudan

Sudan would increase small arms supplies and other support to the South Sudan Democratic Army (SSDA) to cause disruption and further destabilise Jonglei; threaten pipeline shutdown; harden its position over temporary administration and referendum in Abyei; and provide greater incentives for and concessions to Chinese investment.

China

China would increase efforts to improve diplomatic outreach to South Sudan and examine further strategic investment opportunities associated with the LAPSSET, while at the same time maintaining strong diplomatic links with Khartoum in light of a continuing reputational stake in Sudan’s economic and political stability.

Kenya, Ethiopia and other potential pipeline partners

Potential regional pipeline partners would leverage construction as a means of expanding regional economic and political power and hydrocarbon industry investment, though Kenya and other potential LAPSSET partners would be spurred into debate over strategic refinery construction in East Africa.

***

I. Likelihood of alternate oil pipelines from South Sudan

Oil resources have been a continual point of contention on South Sudan’s path from 22 years of civil war to autonomy under the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and finally secession in July 2011. After the CPA, the 500,000 barrels per day (bpd) oil production was split 50/50 between north and south, but upon secession, South Sudan took a 75% stake in the oil fields. Mutual dependence remained, however, due to Sudan’s ownership of midstream oil infrastructure (the pipeline from South Sudan to Port Sudan on Sudan’s Red Sea coast and three oil refineries).

Post-secession, the two governments were unable to agree on pipeline transit fees which led to South Sudan reneging on the $32-36 per barrel transit fee. In response to non-payment, Khartoum seized over $815 million in oil revenue and began diverting South Sudanese oil to its own refineries. In January 2012, Juba countered by shutting down its 350,000 bpd of oil production and export.

The shutdown enflamed existing hostilities and military offensives were launched by Sudan and South Sudan near the Heglig oil fields in March and April 2012. Both countries experienced significant economic deterioration as oil revenues made up a majority of government revenues (98% of South Sudan’s revenue and 50% of Sudan’s revenue in 2011). Inflation and currency devaluation plagued both nations and government austerity measures created political instability, particularly in Sudan.

Throughout the production shutdown, efforts to commission an alternate pipeline gained greater prominence in South Sudan. Concurrent with the oil shutdown resolution, a second cabinet resolution was adopted to seek out an alternate pipeline route. South Sudan initially sought a pipeline route as part of the $29.24 billion Lamu Port-Southern Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPPSET) Corridor Project; however, a second alternate pipeline route through Ethiopia to the Port of Djibouti is also being evaluated. There are also a number of alternate configurations of these two main proposed routes.

Since January 2012, South Sudan has negotiated multiple memorandums of understanding and intergovernmental agreements with Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti to progress pipeline feasibility studies and broader economic integration issues. In tandem with these agreements, President Salva Kiir initiated a programme of financier outreach, seeking project finance from Asian and Gulf State countries and international finance institutions.

Media reports have suggested that construction of a South Sudan-Port Lamu pipeline is slated to begin in October 2013. However, this is unlikely given some feasibility and environmental assessments remain outstanding and have not been subject to evaluation and review, project financing is yet to be identified, further intergovernmental agreements are incomplete, and another route – to Port of Djibouti – is also on the table. There are six macro-environmental factors important in this assessment, which are considered in the following pages:

- Sudan-South Sudan relations

- Project economics, finance and insurance

- Security along the proposed pipeline routes

- Environmental and geotechnical challenges

- Views of key oil purchasers

- Regional political dynamics

a. Sudan-South Sudan relations

South Sudan’s desire for an alternate pipeline primarily boils down to poor relations with its northern neighbour and a fear of economic strangulation by Sudan. Economic independence from Sudan is perceived as a crucial foundation for the South’s newfound statehood. After almost 15 months of oil production shutdown, both parties signed an Implementation Matrix on 12 March 2013, which gave life to the 27 September 2012 agreements between Presidents Kiir and Bashir. Oil production and transport restarted, transit fees were renegotiated to an average $9-10 per barrel, a demilitarised buffer zone along contested border regions was agreed to and temporary administrative arrangements for Abyei were documented.

Some analysts, diplomats and executives interpreted the agreement and Bashir’s first post-secession visit to Juba as evidence of a possible lessening of antagonism between the two countries. The demands for an alternative oil pipeline quietened, as these developments were seen as the first tentative steps towards normalisation of relations.

It is more realistic, though, to see the agreement as resulting from domestic, internal pressures rather than a dilution of the underlying mistrust and disagreement. This would be consistent with a number of previous agreements between the north and south, where parties aimed to consolidate or stabilise domestic support while deferring contentious issues or embedding ambiguity to secure political and military flexibility.

Bashir’s recent adoption of the flagship policy postures of Vice President Ali Osman Taha in the face of increased factional isolation, economic instability and multiplying internal regime change threats are of note. The gradual release of political opponents from detention, initial openness to African Union-sponsored talks with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM–N) and a planned high-level delegation visit to Washington show a very different, more reform-minded and less hawkish Bashir. This stands in stark contrast to the hardline rhetoric he deployed while rallying against the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) and New Dawn Charter some months earlier.

Kiir similarly faced increased domestic pressure for lessening conflict with Sudan, with unpaid military and public sector wages becoming a security liability. Even with financial support from international donors and new foreign direct investment, economic deterioration in South Sudan rivalled that experienced in Sudan. Juba needs oil revenue for critical infrastructure investment and thus agreement with Khartoum is beneficial, at least for the short term.

Indeed, north-south normalisation is likely to only be a short-term prospect, as evidenced by new threats from Khartoum to shut down pipeline operations and suspension of peace talks with SPLM-N. Current agreements are more accurately characterised as a strategic retreat by both parties to move out of economic red zones and stabilise domestic support. Over the longer term, the underlying drivers motivating Juba to seek alternate pipeline routes remain.

b. Project economics, finance and insurance

Proven reserve estimates for South Sudan range from 4.2 billion barrels to 6.7 billion barrels (2012 figures) and industry analyst consensus leans towards these been insufficient to justify a second pipeline. IMF projections suggest that, without any new discoveries, South Sudan oil production is likely to decline by 50% over the next 10 years. At historical production rates, existing fields will be depleted in 20-30 years. (These estimates do not fully account for excessive oil production rates between 2005 and 2010 that may have compromised maximum field recovery rates.)

There are a few variables which would alter this assessment. New domestic exploration that resulted in large discoveries would make a stronger case for an alternate pipeline. To this end, the proposed carving up of Total SA’s exploration licence in Block B was not only aimed at generating revenue and bringing US oil and gas interests back into South Sudan, but also at spurring competitive exploration activity. Similarly, attempts were made to generate government income during the shutdown by offering new exploration licences to a range of private and state-owned national oil companies.

Significant new discoveries contiguous to the proposed pipelines routes in northwest Kenya or Uganda would also improve project economics. The Ugandan government is in ongoing negotiations with joint venture partners Tullow Oil (Ireland), CNOOC Ltd (China) and Total SA (France) for a 120,000 bpd pipeline to export its 3.5 billion barrels of crude reserves via the East African coast. Tullow has also made new discoveries in Kenya’s northeast Turkana region. Taking account of increasing exploration activities in Eastern Africa and multinational oil companies operating on regional basis, new discoveries in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia are highly likely to improve project justification. However, domestic economic development imperatives and regional competition for refinery infrastructure, particularly between Uganda and Kenya, could possibly overshadow improved economics.

A key impediment is Juba’s access to finance. A number of potential financing partners are unenthusiastic about Juba’s alternate pipeline proposal. The IMF’s less-than-successful experience with the Chad-Cameroon pipeline, the high project risk, South Sudan’s poor fiscal position and the highly politicised nature of supporting an alternate pipeline with concessional finance have kept international financial institutions such as the African Development Bank and International Finance Corporation at bay. China’s rejection of Kiir’s financing requests is likely based on its diplomatic balancing act and the outstanding debt repayments owed on Sudan’s pipeline and refinery infrastructure. Alternative financing options, such as national infrastructure bonds and public-private partnerships, at this point seem unlikely to raise sufficient capital and build-own-operate–transfer (BOOT) concessions with pipeline developers would put a premium on investor returns due to project risk. A BOOT structured arrangement with Japan’s Toyota Tsusho Corporation, who successfully bid on pipeline construction, remains a possibility.

East and Southeast Asian crude importers such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore would be more likely contenders for financing roles but only if South Sudan’s fiscal position improves and Juba achieves partial normalisation of relations with Khartoum. Kiir’s May 2013 visit to Japan to explore investment opportunities for Japanese companies may indicate that Shinzō Abe’s government is open to exploring pipeline financing options.

Project costs are highly likely to be further inflated by the insurance coverage necessary to cover project risks such as infrastructure sabotage, environmental damage and operational shutdowns. Private insurance markets would, however, be unlikely to provide insurance. Instead, state-owned export credit agencies would most likely step in to provide concessional access to insurance, leading to a degree of politicisation of project financing.

c. Security along the proposed pipeline routes

Armed conflict, infrastructure sabotage, military operations and intercommunal fighting have all impacted oil industry operations in the region. There are multiple points along the proposed LAPSSET route where the pipeline would come close to areas that are historically subject to conflict and violence, but the proposed route does not traverse areas of concentrated conflict and violence (particularly in Kenya).

These maps are based on data collected as part of the Peace Research Institute Oslo’s Armed Conflict Location and Event Data for Kenya, South Sudan and Sudan (1997-2012) and visualised in Google Fusion Tables. The metadata for each plotted conflict is available at http://bit.ly/15oTowq. Higher resolution maps are available at http://bit.ly/10Ex0ze.

South Sudan will most likely experience armed conflict and violence in oil production fields in Jonglei and Unity. David Yau Yau’s South Sudan Democratic Army (SSDA) with support from Khartoum are likely to engage in armed activities to disrupt construction and operation. Targeted Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) attacks on oil production infrastructure are unlikely, although they become more likely if demilitarised border zones collapse and political disputes over Abyei intensify. Even then, though, the SAF would have some incentive to not attack oil infrastructure due to the implications for its relationship with Chinese, Indian and Malaysian oil producers.

In Kenya, armed conflict threats along the proposed pipeline route – particularly if the route heads due east after Lake Turkana as opposed to heading further south then due east to Lamu – are limited. The Tana River area has the highest threat throughout the proposed routing with widespread violence and crime reported in the run up to the 2013 elections. Elsewhere, there is no open source intelligence to suggest that the routing of the pipeline should affect the tribal dynamic in any way. The majority of the arable land is in southwest Kenya so its routing will not affect land use to any great degree. It is assessed that any violence or crime will be localised and petty in nature, rather than as the result of organised crime.

The project footprint of the Port Lamu development will most likely have a significant impact on the local Lamu community. There is low-to-medium probability of the pipeline’s connection to the Port Lamu development and proposed refinery becoming a conflict risk multiplier through conflict over project revenues, transit fees, relocation and compensation. While the limited land use conflict potential between the pipeline and local community economies in key Kenya counties – Turkana, Samburu, Isiolo and Tana River – is low, there is a much stronger potential for conflict between the local fishing and tourism economies of Lamu and port redevelopment.

d. Environmental and geotechnical challenges

Pipeline construction and operation projects experience environmental and geotechnical challenges that shape project economics and operational risk. Feasibility studies by Toyota Tsusho (Port Lamu pipeline) and ILF Consulting Engineers (Ethiopia-Djibouti pipeline) will highlight the specific environmental and geotechnical issues associated with the proposed routes.

For example, pipeline crossings over parts of the Sudd Wetlands in South Sudan – some of which are Ramsar-listed Wetlands of International Importance – are likely to raise concerns about potential spill impacts for inland fisheries and agricultural production. Addressing pipeline spill threats to the Sudd Wetlands ecosystem could require substantial and costly engineering solutions.

At Port Lamu – a UNESCO world heritage site – a coalition of community and environmental groups operating under the umbrella of Save Lamu and the WWF have raised a number of concerns with the Port Lamu proposal, including resettlement issues, water rights, compensation, economic development opportunities and environmental damage. Port Lamu locals and Save Lamu groups have sought injunctions against the project before the Supreme Court and participated in protests at the Kenyan Ports Authority.

e. Views of key oil purchasers

Related to financing options and project economics are the different commercial objectives, expectations and rights of oil producers and buyers. Key purchasers of Sudan/South Sudan oil exports include China (purchasing 66% of all oil exports in 2011), Malaysia (9%), Japan (8%), UAE (5%), India (4%) and Singapore (4%). At 260,000 bpd, Sudan/South Sudan export oil made up 5% of China’s total imported oil in 2011.

Despite South Sudan only producing 0.3% of total global oil production in 2011, the 2012 production stoppage may have caused some oil price pressure, particularly for Asian buyers seeking the Dar and Nile blends of crude oil. However, buyers focussing on short-term supply security concerns as opposed to longer-term horizons are still unlikely to support an alternate pipeline route. Although an alternate pipeline would diversify delivery options and spread disruption risk, many buyers are invested in the commercial success of Sudanese midstream production infrastructure, reduced use of which would impact Sudan’s ability to service refinery infrastructure debt. However, each major buyer will have a different perspective.

China’s current preference for oil transportation via the existing pipeline to Port Sudan is likely based on a combination of avoiding a Sudan-South Sudan zero sum game, securing operations for upstream refineries and resuming oil export. This is likely being leveraged through aid contributions, economic assistance and development support, which may include an alleged $8 billion dollar aid/development pledge to South Sudan. India and Malaysia, whose state-owned oil companies have large stakes in key oil production companies such as Greater Nile Petroleum Operating Company, Petrodar and White Nile Petroleum Operating Company, are possibly emulating Sino diplomacy over the short term.

Japanese buyer interests may diverge from other buyers. Toyota Tsusho’s $5 billion bid to build the South Sudan to Port Lamu pipeline, the reported willingness of Japanese private financiers to fund pipeline construction, and increasing Japanese demand for Nile blend could mean Japanese buyers may be more supportive of alternate pipeline proposals. June 2013 reports suggest that Kiir and Toyota Tsusho’s chairperson, Junzo Shimizu, had a successful meeting on the Lamu pipeline and demonstrate strong Japanese interest in an alternate pipeline, although it remains unclear whether any agreements on project financing have been made.

f. Regional political dynamics

Infrastructure development proposals such as the LAPSSET corridor, of which oil transportation and refining are components, will involve substantial reordering of political relations through regional economic development and integration. Through South Sudan’s strategic economic and regional geopolitical realignment, broader political and economic objectives may trump the importance of pipeline economics.

The LAPSSET project is anticipated to open up agricultural and manufacturing market opportunities and establish new supply chains across South Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya. LAPSSET Infrastructure development, which includes Port Lamu development, fibre cable networks, new road and rail networks, and regional airports, envisages Kenyan coastal access to export markets and is touted as a key economic growth driver for the region. Project economics for an alternate pipeline to Port Lamu in its own right might not stack up, but pipeline economics may substantially improve if evaluated as part of an integrated and interdependent infrastructure development programme.

In addition to improving project economics, politicised concessions in the name of regional trading unity are possible. South Sudan’s eagerness to join the East African Community (EAC) is indicative of Kiir’s plans to ensure South Sudan is part of a regional political order that is not hostile to its ethno-religious and cultural values and is slated for significant hydrocarbon-sparked economic growth.

South Sudan’s acceptance into the EAC and expanding relations with Kenya, Ethiopia and Uganda is likely to improve the prospects for alternate pipelines. While EAC economic integration is likely to increase the prospect for a politicised decision to actively and financially support pipeline construction, politicised support may be tempered to some degree by the Kenyan and Ethiopian caution in avoiding deterioration in relations with Khartoum. One reason for caution may be the potential for some Muslim groups such as Al Shabaab to cast deterioration as a transboundary, anti-Islamic political agenda, whereby LAPSSET is a vehicle to punish the Muslim North in favour of the Christian South. Competition between alternative pipeline proposals (to Port Lamu or Port of Djibouti) and Uganda-Kenya pipeline negotiations suggest a state of flux for regional relations and the inherent competition to host key hydrocarbon infrastructure. Additionally, alternative visions for regional economic integration – South Sudan (oil) and Ethiopia (hydropower and water regulation) – could compete for South Sudan’s attention, especially considering the benefits to South Sudan of closer relations with the militarily-strong Ethiopia.

South Sudan, despite enthusiasm for participating in EAC, could possibly adopt a more sober examination of the short-term downsides associated with EAC participation. South Sudan’s economy is frail and its industries in embryonic stages of development. Competing in free and open regional markets whereby other participants have significantly stronger economies and industry may cause domestic economic shocks for South Sudan.

Longer term, the potential for large integrated hydrocarbon industry development concurrent with agricultural modernisation across East Africa may spur a repositioning of Chinese diplomacy and investment strategy aimed at greater participation – alongside other Asian and US interests – in East African markets.

II. Stakeholder impact of alternate pipeline construction and operation

Relations between Sudan and South Sudan are in a state of flux and dogged by significant uncertainties. This combined with the involvement of multiple regional stakeholders with diverse interests, results in limited confidence levels for forecasts of potential responses to alternate pipeline construction. Proposed pipeline construction and operation would most likely have regional significance, if oil transport through the northern pipelines is reduced to a nominal amount. An alternate pipeline will almost certainly reconfigure relations, alter investment priorities, reshape diplomacy and shift security preoccupation. While the specifics of how this complex matrix of interests will be impacted is difficult to forecast, some general trends and possible stakeholder responses can be identified.

South Sudan

The primary impacts on South Sudan may include:

- Depending on project financing, pipeline construction may put substantial pressure on South Sudan’s fiscal position at a time when critical government and social services are kept afloat by official development aid and economic assistance from abroad – posing a real economic threat to South Sudan during an embryonic stage of development. The fiscal position may even worsen if Sudan does not achieve Heavily Indebted Poor Countries status and gain access to debt relief. In this scenario Sudan’s large external debt burden will most likely be shared with South Sudan.

- Conflict and displacement in Jonglei and Unity will need to be addressed through proactive measures to assure financiers that project-related conflict is minimised. This would require significant political capital, financial resources and support services that have not thus far been deployed to engage with rebel groups such as SSDA.

- While a more sober assessment of the East African Community is required, pipeline construction may put increased pressure on Juba to participate and implement the EAC treaty requirement if project concessions are made by Nairobi to achieve regional economic integration objectives.

- Relations with Khartoum would be impacted and Juba could expect to face a hardened bargaining position on Abyei and increased breaches of the demilitarised zone.

Sudan

Sudan would be significantly impacted if an alternate pipeline severely diminished crude transport. In response, Khartoum may:

- Provide reinvigorated but covert support to proxy rebel groups such as the SSDA in Jonglei state to disrupt construction and discourage financier investment (increasing project insurance costs).

- Possibly attempt to exert diplomatic pressure on Chinese representatives to discourage Juba from alternate pipeline construction; possibly offering new concessions for increased Chinese investment as an alternative to increased Sino investment in LAPSSET infrastructure programmes.

- Harden its position on the administration of Abyei and reverse the limited progress made in the September 2012/March 2013 agreement in terms of existing border disputes.

- Put more focus on securing debt relief and developing alternate government revenue sources, including domestic hydrodam development, mining and agricultural exports, to address revenue gaps and debt servicing obligations that would be impacted by oil revenue loss.

China

Upon confirmation of pipeline construction and commissioning, Chinese state-owned companies and government officials may possibly:

- Continue to balance Sudan-South Sudan relations but in the event of further CNOOC-associated discoveries in Kenya and Uganda may quietly advocate for a new pipeline. This limited support for a pipeline would be conditional upon the existing pipeline in the north still carrying significant crude reserves.

- Make efforts to improve South Sudan diplomatic outreach and examine further strategic investment opportunities associated with the LAPSSET project and East African hydrocarbon exploration and production opportunities.

- Maintain strong diplomatic links with Khartoum and continue to have some reputational stake in Sudan’s economic and political stability, but could possibly reduce the level of financial assistance provided to Sudan and infrastructure investment over the long term.

Kenya, Ethiopia and other potential pipeline partners

Kenya and other potential LAPSSET partners involved in pipeline construction are likely to:

- Seize upon pipeline construction as concrete evidence that LAPSSET and the Kenya Vision 2030 are viable regional economic integration and growth measures.

- Instigate further debate and dialogue on strategic construction and installation of refinery capacity and increase regional political competition over the short term until plans for hydrocarbon infrastructure configuration are settled.

- Respond to project-related conflict and protest with pledges of new investment and infrastructure provision for affected regions.

Source: Open Briefing (United Kingdom)